Bradbury, Ray. Fahrenheit 451. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018.

I mentioned

before that I was reading or re-reading many of the works of Ray Bradbury. I wasn't reading them with a specific eye to Shakespeare, but he seemed almost inevitably to make his way in.

In Fahrenheit 451, I found a fair bit more Shakespeare than I expected. But I suppose there’s quite enough radical or subversive or even offensive material in Shakespeare to make his works catch the eye of any fireman worth his salt.

For this rest of this post, I’m going to assume a basic knowledge of the plot and characters of the novel. If you’re unfamiliar with Fahrenheit 451, I’ll wait while you grab a copy and read it through. Even if you take your time (which you should), it won’t take long.

The first Shakespeare reference comes when Captain Beatty provides a brief history of the firemen as something of a pep talk to Guy Montag when he seems to be suffering from cold feet:

It's terrifying to imagine a world where a one-page

Hamlet is all people think you need. But Shakespeare does inspire thought—and independent thought is certainly dangerous.

Beatty's speech constrains Montage for a while, but only for a while. Later, when Montag more or less makes up his mind to find out what uses books might have and realizes that he needs a guide or a teacher if he's to answer that question with any kind of thoroughness, he remembers a man named Faber that he met by chance one day:

Montag decides to give the professor a call to ask about, among other things, Shakespeare:

Later, as he attempts to make a plan with Professor Faber to return the world to the state it was in before book burning took over, the professor talks about actors unable to play Shakespeare and how they might become part of a proposed underground:

Unfortunately, this vision isn't fuffilled within the covers of

Fahrenheit 451.

It's not long before Beatty finds out that Montag has been hiding books. He talks him round, and Montag hands over a book. We get an adapted Shakespeare quote at that point (and some Donne):

The first quote is a modified version of a quote from

As You Like It—it’s what Jacques says on the entrance of Touchstone and Audrey: “Here comes a pair of very strange beasts which in all tongues are called fools” (V.iv.9–10). The second quote is from the end of John Donne’s “The Triple Fool.”

A bit later, a torrent of allusions and quotations comes from Beatty (while Professor Faber listens in through an earpiece Montag is wearing):

It's hard to catch the teaspoons of Shakespeare in the midst of that firehose (sorry!) of literary allusions and quotations. We have, among other things, the Bible, Sir Philip Sidney, Alexander Pope, Samuel Johnson, Ben Jonson, Francis Bacon, and Thomas Dekker. It's almost like one of T. S. Eliot's poems!

For everyone's convenience, here are the Shakespeare quotes, misquotes, and allusions:

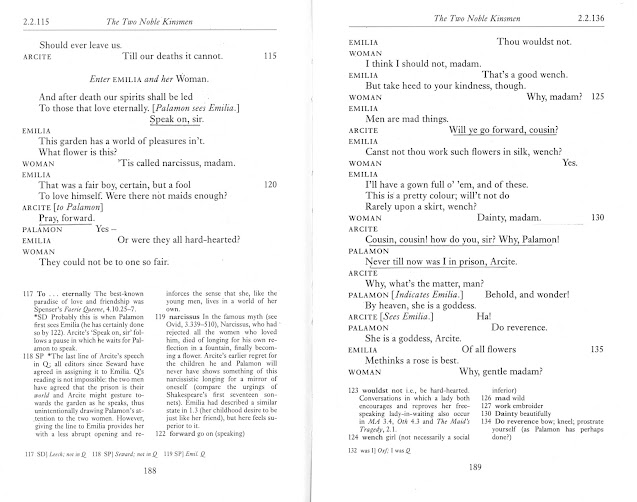

"Nay, it is ten times true, for truth is truth / To th' end of reck'ning" is one thing Isabella says about the crimes Angelo has committed in Measure for Measure (V.i.45–46).

"Truth will come to light; murder cannot be hid long" is from Launcelot Gobbo's exchange with his father in The Merchant of Venice (II.i.79).

"Oh God, he speaks only of his horse!" is a rough paraphrase of a line Portia speaks to Nerissa about one of her suitors: "he doth nothing but talk of his horse" (Merchant of Venice, I.ii.40–41).

"The devil can cite scripture for his purpose" is what Antonio says to Bassanio about Shylock in The Merchant of Venice (I.iii.98).

"A kind / Of excellent dumb discourse" is from The Tempest (III.iii.38–39): Alonso is speaking of some magical figures Prospero has conjured up to bring in a meal. Is the "Willie" at the end of Beatty's speech addressed to Shakespeare? Montag's first name is "Guy," not "William" after all.

"All's well that is well in the end" might be a version of the title of the play All's Well that Ends Well or the titular line that appears twice in the play. Helena says, "All's well that ends well! still the fine's the crown; / What e'er the course, the end is the renown" (IV.iv.35–36); a little later, she says, "All's well that ends well yet, / Though time seem so adverse and means unfit" (V.i.25–26). But it could also be a skewed version of Julian of Norwich's mystical pronouncement "All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of things shall be well."

I find it interesting that the imagined exchange between Montag and Beatty involves throwing quotes specifically from Merchant of Venice at each other.

More than that, we have an awful lot of famous quotes taken far out of context and put together in a way that is only roughly and somewhat incidentally meaningful. It underlines Montag's instinctual assumption that possession of texts is not enough—comprehension of them is another essential element.

We get one more quotation from Shakespeare in what turns out to be Beatty’s last speech.

The quote is from

Julius Caesar—it's Brutus speaking to Cassius in Act IV, scene iii (lines 66 to 69, for those of you keeping score), when their backs are up against the wall and their hackles up against each other. Eventually, Cassius and Brutus reach an uneasy peace, but it's not so with Beatty and Montag. It's at this point that Montag thinks he might be able to burn

right by burning one of the chief book burners of them all.

It ought to go without saying, but I'm worried that it doesn't: Bradbury demonstrates astonishing mastery in creating Beatty, who knows a huge number of bits and pieces of what oft was thought but ne'er so well expressed and who uses them to overwhelm a novice—a freshman English major—a second-hand (but not second-rate) literateur.

At the end of

Fahrenheit 451, we're left hoping for those actors Professor Faber spoke of to produce, by memorial reconstruction if by no other means, the complete works of Shakespeare, without which our lives would far more dystopian than not.

Click

here to purchase the book from amazon.com

(and to support Bardfilm as you do so).